Episode 1 – Wilpattu National Park

My encounter with an elephant

As I recall, this incident occurred in February 1984. Our mission was to capture an elephant in theGalgamuwa, Ras Vehera region, then transport it to a different location after loading it into a truck. I was a recruit with nearly two years of experience. Prior to this mission, my work was involved in elephant chasing, so capturing and transporting an elephant was my first task of such nature.

The elephant had to be captured in the area of Kannoruwa tank. During that time, the area was not declared as a reserved forest. It was under the Mahaweli Project.

This elephant had garnered itself an infamous reputation. It was responsible for the deaths of 2-3 people and a significant amount of property damage in the area.

Including me, around 20 officials, some with experience such as Mr. Bahaman and Mr. Mansoor, were assigned to partake in this endeavor.

On the day of our mission, The elephant had returned to the forest after a rampage which resulted in considerable property damage in the village. We knew this elephant was undergoing Musth, which made it dangerously aggressive due to increased levels of reproductive hormones. Quietly and diligently, we followed its trail of footprints. After about half a kilometer into the ‘Andara’ (dense and thick) forest, we understood that this beast is approaching its herd. Suddenly, Mr. Mansoor signaled the presence of the elephant.

We heard a loud, angry trumpet and saw the elephant charging towards us from about 50-60 meters away. The elephant had picked up our scent because of the change in direction of the wind. We fired loud crackers to scare the beast away, but it kept continuing its warpath, drawing closer and closer to us every second.

Our group began to scatter and retreat. I was in the very front, fearing for my life with every passing second as this enraged, gigantic animal drew closer and closer, when as luck would have it, I noticed a large ‘Palu’ tree nearby. I ducked and cowered beneath the tree. I had barely begun to regain my senses when I felt a powerful gust of wind almost knocking me over followed by a thick spray of mud. I had barely gotten out of its way when the elephant had jumped over me and landed with such force that its coating of mud rained over me.

After a while, when I could no longer hear the elephant, I heard the faint and panicked voices of my colleagues, anxiously reassuring each other and inquiring about injuries any of us have sustained. I noticed that part of the long-sleeved shirt I was wearing was caked in mud, with a partial imprint of an enormous elephant’s footprint. The angry giant had missed me by mere inches. I survived.

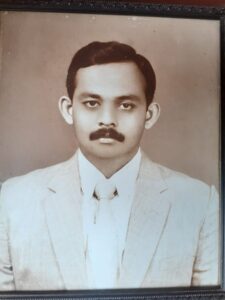

Vehan Sahanjith Weragama

Vehan Sanjith Weragama joined the Department of Wildlife Conservation on November 1981, as a 3rd Grade Ranger when he was less than 20 years of age. After passing his first and second efficiency barrier exams, today, he serves as an Assistant Secretary of the Anuradhapura Division. His loving family consists of his wife, daughter and son. They reside in at Galagedara in Kandy, whereas Mr. Weragama conducts his duties while staying in the Anuradhapura quarters.

Wilpattu National Park

Wildlife Reserve areas in Sri Lanka were declared under the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance in 1938. The wildlife reserves are divided into several categories.

1) National Parks

2) Strict nature reserves

3) Nature Reserves

4) Sanctuaries

The first three sections include only government lands and are known as “National Reserves”. A sanctuary can include both government and private lands. Currently, about fourteen percent of the island’s total land area is declared as “wildlife reserves.” Of these protected areas, the National Parks are the closest to the public. This is because the public has been provided with the necessary facilities to see and enjoy the animals that live in them. There are twenty-six national parks in Sri Lanka. Wilpattu Park is also considered a “National Reserve” as it includes only government lands. The distance from Colombo to Wilpattu National Park is about 180 km.

Park Head Office

The “villu” is land that is too swampy to cultivate. This low-lying area is surrounded by an elevated area like a high wall and in the middle is flooded during the rainy season. “Pattu” is a set of villages, several sub- divisions or divisions. Accordingly, this area is called “Wilpattu” due to the presence of many villus.

Wilpattu is divided into two sections for ease of management

1) Wilpattu National Park

11) Wilpattu North Sanctuary

The area of Wilpattu National Park is 131667.1 hectares. The extent of Wilpattu North Sanctuary is 624 hectares.

These lands are generally grasslands, jungles, sand dunes, lakes and tanks. During the months of January-February is a dry season while it experiences inter-monsoon rains from March to April. From May to early September there is a wet dry climate with a long dry season. Then it rains for the whole period from September to December. The average annual temperature is 27 Celsius while annual rainfall is 1000 mm.

There are about 40 Villus within the Wilpattu. These are mostly freshwater bodies. Some of these are saline, although not superficially associated with the sea. The wide sloping beaches around the villus are home to a wide variety of aquatic birds and mammals and are called valuable “feeding areas.” These are known as the main villus.

The swamps in the Wilpattu National Park can be defined as the flood plains separated from the periodically dry rivers. It has been identified that the limestone located in an area of approximately 24 km from the coast is different from the limestone found in the Jaffna Peninsula. The western strip of the lowlands is also composed of sea sand and is rich in sedimentary rocks. The sand and red clay rocks between Palagathurai and Kudiramalai are also rarely found in other parts of Sri Lanka. The central area is abundant with natural water holes and Villus.

The soil in the western hemisphere is very barren with reddish-yellow markings. It is low in organic and mineral substances. The soil in the eastern region is fertile and contains mineral deposits. They are reddish-brown in colour.

Point Kudiramalai

Geographically, it is located 30 km west of Anuradhapura on the North-West coast. It also extends across the border between the North Western Province and the North Central Province. It is bounded on the north by the Modaragam Aru, on the south by the Kala Oya, on the west by the Portuguese and Dutch bays, and by the open sea. The sanctuary, from the coast to the interior, located entirely within the Northern Province. It is adjacent to the park and is separated by the Modaragam Aru.

Wilpattu is also considered as a historical land of Sri Lankans. That is with the accidental landing of Prince Vijaya at the port of Thambipanni or Kudiramalai, a border of Wilpattu. Accordingly, not only the origin of the island’s settlements but also the foundation of the state culture may have fallen in this area. Wilpattu in Anuradhapura, Puttalam and Mannar districts is rich in ancient ruins, legends and folklore.

Ruins of the Kuveni’s Palace

According to legends, the ruins of the palace of Kuveni who wed to Prince Vijaya can be seen today in the “Kali Villu” area. According to a book authored by Ven. Ellawala Medhananda Thero, the palace where King Saliya, the son of King Dutugemunu, and his bride Ashokamala, who lived two thousand years ago, are said to have lived, the water pools, the ruins of the royal pavilions, etc., are also still exist at the Weerangoda and Galbendi Thiraya areas in the northeastern part of Maradanmaduwa. Namely, the kingdom of Viladagoda, built around 161-131 BC, is also located in this area. This Kingdom is located at Aluthgama Junction, about 17 miles from Puttalam-Anuradhapura Road, at the border of the Wilpattu Sanctuary. This is a special place as there are many historical Buddhist relics here including the “Viladagoda” temple built by Prince Saliya. There are also stone pillars, caves of various sizes, cave drips andmonolithic inscriptions in Brahmi script etc.

The Pomparippu area which belongs to the Wilpattu National Park is also an area with archaeological importance. The reasons primarily influenced for the selection of the area for excavations are:

1) It is located very close to the Indian mainland and therefore, to obtain reliable data on what happened during the cultural periods of the island due to the constant cultural and trade relations between the two areas from via the harbour and the north Indian coast.

11) Ecological similarity that have frequently caused the migration and establishment of settlement of the agricultural communities.

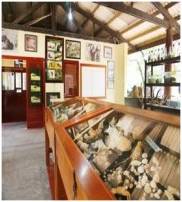

The area near the west coast of the northern part of the island is known as a prehistoric cemetery. This is a protected area located in the dry zone and can also be reached by a road from Puttalam to Ilavankulam. It is bound Kala Oya by south and the ancient Galge Vihara by the east. Most of the cemeteries in Pomiparippu are extensive. Excavations have also unearthed potteries with ashes. Through this research it was possible to get some idea of the technical knowledge of the people at that era. The ruins of an ancient temple at Point Kudiramalai have also been found and the ruins of the Palagathurai harbor used for shipping have also been found. Today, there is an ancient church that holds annual rituals. From the above information it can be seen that a lot of important historical records and monumental inscriptions and ancient fields, monuments and human cultural objects are hidden in the Wilpattu area. Therefore, Wilpattu National Park is one of the oldest and most important protected areas in Sri Lanka.

In terms of flora and fauna, due to the forests in the Western side, bushes, grasslands, and villus in the middle of the park and drainage systems in the center of the park, there is high biodiversity and ecological value here. It is home to 31 species of mammals, including Rhodentia sp. and Chiroptera sp., endangered mammals including elephants, bears, leopards and wild buffaloes. Among the herbivores, the elephant is the least densely populated, followed by the spotted deer. It is around 3,500 in numbers. Meanwhile, under the sanctuary management of the National Park, attempts have recently been made to make the elephant habitats suitable (enrich) for the animals by cultivating grasses etc. Also, populations of local and migratory birds can be seen here.

A Sleeping Leopard (Panthera pardus kotiya)

Bear (Melursns ursinus)

Sambar (Russia unicolor)

Considering the vegetation in this area, there are 3 types of vegetation namely coastal grassland, lowland and coastal vegetation. About 73% of the park is forested or scrublands and the rest is open habitat. The coast is about 5 Km in extent and is a low-lying area while rain forests can be found in the middle with grown trees.

The major western endemic plant species in the park are phoenix sp., unchi, thelkaduru, kolon, wewarana, halmilla, satin, lolu, ebony, daluk, weera, palu, kon, mahadan, milla, kirikon etc.

Shrubs include Heerassa, Damaniya, Bu Kombe, Karapincha, Nelli, Ulkenda and Kukurumana.

Grasses and herbs can be identified as thora, mayura grass, heen grass etc.

The Wilpattu National Park, which has such an aesthetic and historical value, has suffered some damage due to terrorist activities in the past but improved roads built for military purposes, illegal logging and poaching. Expansion of settlements also threatened the integrity of the park and the invasive vegetation in the rehabilitated Maha Andaragollewa and Mahawewa reservoirs was detrimental to wildlife.

Moreover, Wilpattu National Park is managed by the park headquarters at Hunuwila village while eco-tourism activities are also successfully implemented.

Editor – Dhammika Malsinghe, Additional Secretary, Ministry of Wildlife and Forest Conservation (MWFC)

Article on park written by – Hasini Sarathchandra, Chief Media Officer, Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWLC)

Tamil Translations – A.R.F. Rifna, Development Officer, MWFC

English Translations (Documents) – Asoka Palihawadana, Translator, MWFC

English Translations (Story) – Thanuka Malsinghe

Web Designing – N.I.Gayathri, Development Officer, MWFC

Photography – Rohitha Gunawardana, DWLC

Sinhala typing & other assistance – Aruni Palapathwala, MWFC