EPISODE 12 – Sand Dune Islands

Conserving Sri Lanka’s Marine Ecosystems

I joined the Department of Wildlife Conversation in 1999 as a Ranger after getting through a grueling, competitive all-Island examination. After joining, I served in the Wasgamuwa, MaduruOya, Girithale, and Kaudulla national parks before earning an opportunity to serve as the Assistant Director (Natural Resources) at the Colombo Head Office. In 2013, I left Sri Lanka for further studies and did not return until 2015.

Before 2015, there was no specific governing agency for marine life conservation in Sri Lanka under the Department of Wildlife Conservation. However, the government was in the preliminary stages of enacting such a program and I was tasked with the responsibility of heralding the whole enterprise. The establishment of an entire marine unit from the ground up was no easy task. A big hurdle to overcome was research; by acquainting our sapling program with renowned institutions, both governmental and non-governmental, and experts on marine life, we were able to cultivate inter-departmental relations and share knowledge and resources.

In the end, our list of allies included several government bodies such as the National Aquatic Resources Research & Development Authority (NARA), National Aquatic Development Authority (NAQDA), Department of Coast Conservation & Coastal Resources Management (CCCRM), Marine Environment Protection Authority (MEPA), Coast Conservation Department (CCD), and the Sri Lankan Navy. We were also successful in establishing ties with the universities of Colombo and Peradeniya, along with several non-governmental organizations such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the Dugong &Seagrass Conservation Project.

Notable persons, without whose contributions this project would not have been a success, were: ArjanRajasuriya on corals, Dr. LalithEkanayaka on turtles, RanilSenanayake on marine mammals, Dr. AshaDevos on whales, Daniel and Nishan of Blue Resource Trust on sharks, Dr. GihanDahanayaka of NARA, Dr. AnandaMallawathanthri of IUCN, Dr. TurneyPradeep of MEPA, and Navy Commissioner Piyal De Silva.

We delved into our work right away by breaking down our analysis on conservation into distinct subgroups. To name a few are: marine mammals, coral reefs, sea turtles, mangrove habitats, and the effect of conservation on Sri Lanka’s tourism industry. Our work was indeed taxing with all the meetings and numerous field inspections, most of which took place under the unforgiving coastal Sun, but the result was worth it. We identified several iconic locations in need of immediate intervention and action to prevent further degradation such as the Kayankarni area in the north of Pasikuda, Batticaloa, and coral reefs in between the KudaRawanaand MahaRawanalighthouses situated near Yalanational park, where thanks to our intervention, these vulnerable areas were declared sanctuaries, and as such, was awarded protection by the state from any detrimental activity harming the ecosystems.

The most prominent example which stands out from the crowd is when our inspections found a significant amount of damage sustained by the reefs surrounding a dune located several kilometres into the sea, off the coast of Kalpitiya. The main reason for this damage is an increase in oceanic temperature. To the alarm of all conservationists, some areas of coral reef were completely decimated, with powerful water currents and excessive commercial fishing exacerbating the already dire condition. All our partner institutions shared our grave concerns, and an emergency was declared. A massive coordination campaign between all departments found us pooling our expertise and resources together to mitigate and alleviate the grim situation in arguably, Sri Lanka’s most splendorous coral reef. We identified places where life is slowly but surely, starting to make a comeback in the defeated and weathered reefs, and placed buoys to deter fishermen.

On a more personal note, an incident vividly seared into my memory is when one typical sunny afternoon found us sailing to the dune for a routine inspection. Once we arrived at our destination, I looked around to find my friend, ArgenRajasuriya – an expert on corals and a skilled diver – who accompanied me on this visit, already off the boat and in the water. I put on my snorkelling gear and was set to jump off the boat and into the water to join him when I slipped and my lower left leg got dislocated from the knee joint, causing me to fall awkwardly into the water. I was barely able to distinguish my colleagues panicking and scrambling to help me, while the excruciating pain in my leg was compounded by struggling to stay afloat, a fact not helped by the unusually strong current. In no time at all, I found myself drifting away from my company, and soon, I couldn’t recognize their faces from the distance, but fortunately, that is where the current ceded to calmer waters. All the time spent diving with Argen in prior visits was not in vain and proved especially handy in coordinating my movements just long enough to stay afloat and pop my leg back into the joint. The burst of agony gradually subsided and I gingerly waded back to my friends with the dawning relief upon realizing that everything is going to be all right.

This is just one story out of many, and I am content because, in the end, everything indeed did turn out to be all right. The newly resurgent coral reefs in the area teeming with life are a testament to the effort and dedication that went into protecting one of Sri Lanka’s most marvellous ecosystems.

Mr. Channa Suraweera

After passing an island-wide competitive examination, Mr. Suraweera joined the Department of Wildlife Conservation as a Grade 1 Wildlife Ranger in 1999, before which he worked as a teacher. He was first appointed to the Wasgamuwa National Park, secondly as the Park Warden of the MaduruOya National Park, while he served as the Resource Person of the Giritale Training Center, then as the Parks Warden of the Kaudulla National Park, and later he served as the Assistant Director of the Natural Resources Division at the Colombo Head Office in 2011.

During the period, Mr. Suraweera, completed a special Diploma in Wildlife Management at the University of Colombo and a nine-month Postgraduate Diploma in Wildlife Management at the National Institute of Wildlife, India. Later he was selected to pursue a degree in Forestry, Water and Landscape Management in the Czech Republic from 2013 to 2015.

Mr. Suraweera was given the opportunity to follow a PhD by the Czech Republic due to his research skills and excellent results. After arriving in the island in 2015, with establishing of the Maritime Unit from that year onwards, he was able to complete a five-year Maritime Management Plan from 2017 onwards. He has been the Assistant Director in charge of the Southern Region since 2020.

Channa Suraweera’s wife is a teacher and they have three children. All three children are still school going. His address is 28D, Walpitamulla, Dewelapola.

Sand Dune Islands

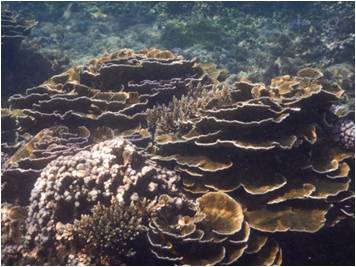

Coral reefs are one of the most biologically diverse and productive ecosystems on Earth and are known as marine rainforests. Coral reefs are like a rainbow of intricately shaped marine life. Coral reefs cover only a small percentage of the ocean bed, but are home to about 25 percent of the world’s marine life.

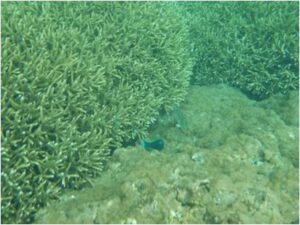

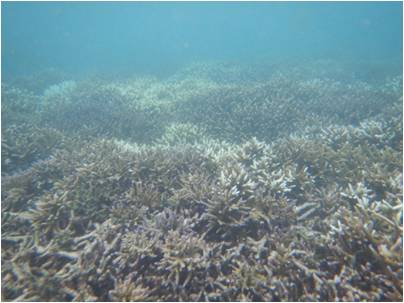

Extensive thickets of Staghorn coral

Coral reefs, also known as ‘Rain forests in sea’, are an underwater ecosystem built up by colonies of tiny creatures called Coral Polyps. These coral reefs gradually form a limestone outer shell on the seabed of shallow coastal waters to protect their delicate structures. Thousands of coral reefs of the same species combine to form a coral colony, and when it becomes a coral reef, different coral reefs are a collection of many species of coral colonies. Many coral reefs contain photosynthetic algae called zooxanthellae, which live in the tissues of multiple corals. There is an interrelationship between corals and algae. Provides an environment conducive to coral algae and the compounds needed for photosynthesis. Algae produce the oxygen and nutrients needed by many and help remove waste. Coral reefs are one of the largest producers of oxygen in the ocean.

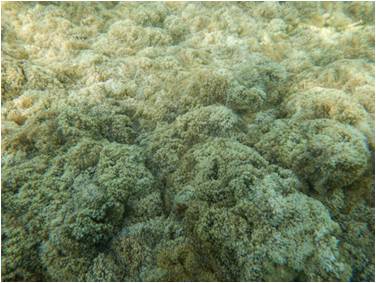

Pocilloporadamicornis at Hambanthota

Corals come in a variety of shapes, sizes, and colors, and there are two types of corals. They are soft corals and hard or strong corals. Coral reefs in Sri Lanka are classified as fringing reefs, patchy reefs, sandstone reefs and rocky reefs. Sri Lankan coral reefs are generally off shore reefs. True barrier reefs do not exist in Sri Lanka, so they are considered close to the shore. They occur in different habitats but are also mixed.

Bar Reef is one of the most famous and largest coral reefs in Sri Lanka. Declared a Marine Sanctuary in 1992, under the jurisdiction of the Department of Wildlife Conservation, it covers an area of 306.7 square kilometers (118.4 square miles), consisting of shallow coral reefs, sea grasslands, and deep sand dunes. This bar reef sanctuary is located in the middle of the sea a few kilometers off the coast, this is a reef complex that stretches from the Northern tip of the Kalpitiya Peninsula to the islands separating the Gulf of Mannar from the Gulf of Portugal. This is an area in the Mannar District of Northern Sri Lanka, close to Jaffna, inhabited by 156 species of coral and 283 species of fish of high ecological, biological and aesthetic importance. Sand Dune Marine Sanctuary (N8 ° 22.57 ‘E79 ° 44.35’) Kalpitiya is the only Marine Protected Areas in Sri Lanka with a depth of up to 3 m, including various marine habitats. Sand Dune Marine Sanctuary covers the northern part of the Kalpitiya Peninsula, the Mutwal Peninsula and the Karaitivu Islands. It consists of 11GramaSevaka (GS – GramaNiladhari) Divisions (the smallest administrative division in Sri Lanka) north of the road that runs east-west to the Kandakuli fishing harbor. Hikkaduwa Marine National Park, Pigeon Island Marine Park, Sand Dune Marine Sanctuary and Rumassala Marine Sanctuary can be identified as the four marine protected areas of the island.

The Kalpitiya sand dune coral reef is the largest spotted reef coral reef. The shores of our island are also surrounded by many coral reefs. With the Kalpitiya coral reef being the largest reef system in Sri Lanka – it plays a significant role in the marine biodiversity of our country.

Coral reefs are beautiful places that offer an entertaining value. After an hour boat ride from Kalpitiya, you can reach the 300 km long Sand Dune Marine Sanctuary, the largest protected maritime area in Sri Lanka. It is best to dive or use a Glass Bottom boat to visit the Welipara Marine Sanctuary. Not only coral reefs but also various ornamental fish can be seen swimming in the coral reefs. Snorkeling is the best way to view shallow coral reefs and fish. Snorkeling is also recommended only for those with good swimming ability. The sand dunes are accessible during the Northeast monsoon season from late October to mid-April, but strong winds can occur during the months of December and early January and can be quite problematic during boating. The best time to visit is February and March, when light winds bring calm sea and good underwater transparency. It is best to try to get there in the morning as the trade winds are high in the afternoon.

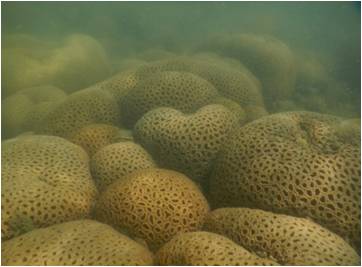

FaviaspeciosaatMoldivabank – Close to Wedithalathive area

The growth of coral reefs around Sri Lanka is mainly affected by the monsoon weather and the increase in turbulent coastal waters during the southwest monsoon season also hinders coral reef growth. Almost all the reefs in Sri Lanka are located within 40 km of the coast and make a significant contribution to marine fish production. These reefs, which create comfortable habitats for a variety of marine life, are home to a number of species of invertebrates, including commercially important thorn lobsters, prawns and crabs, as well as marine grasses and algae. Dolphins, whales and sea turtles are also found along the coast and in the reefs, and several species of butterfly fish have been reported.

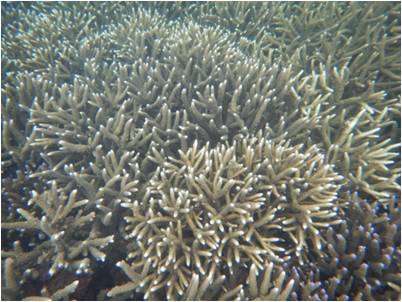

Although the sand dune sanctuary has been in a state of pristine for many years due to limited human population and limited fishing in the area, many of the reefs near the coast today have been severely damaged by human activity. Mainly marine coral mining, destructive fishing practices, fishing gear and uncontrolled harvesting of reef resources have contributed to the overall deterioration of the marine environment. Global warming in 2018-2019 also destroyed many coral reefs in the Sand Dune Marine Sanctuary area.

Legislation to protect marine life in Sri Lanka was enacted over a century ago. All coral species are protected by the Department of Wildlife Conservation through the Wildlife Conservation Ordinance. Areas to be conserved from Puttalam, Kalpitiya to Point Pedro via Mannar have been identified under the project for the conservation of dugong and sea grass. Coral reefs are also protected under the Coast Conservation Act, but are restricted to coastal waters within 2 km of the Medium Low Water Line (MLWL). Several coral reef areas have been designated as National Parks and Sanctuaries. Hikkaduwa National Park, Pigeon Island National Park, Bar Reef Marine Sanctuary and Rumassala Marine Sanctuary can be identified as reefs in the four marine protected areas of the island.

In addition, the 953-hectareKayankarniarea on the 11.04.2019 and the coral reef between the small RawanaMahaRavana lighthouses covering 67,282.3 hectares on 11.10.2019 have been declared enacted as Marine Sanctuaries.

In 1999, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) launched the Coastal Resource Management Project (CRMP) in Sri Lanka and established integrated management to improve the sustainability of coastal resources. It addressed coastal erosion, pollution, unmanaged fishing, over-exploitation of resources and poverty in coastal areas. A Field Project Implementation Unit (FPIU) was set up at Kandakuli to develop a sustainable development plan for the region.

Undoubtedly, it is the duty of each and every one of us to protect such precious natural resources, which are rarer than rainforests.

Staghorn coral (Acroporaformosa) at Pigeon Island National Park

Sources:

Wikipedia

Travel Lanka

Current Status and Resource

Serendib

Springer Link

Time out

SARID

Sri Lanka’s Amazing Maritime

Editor- Dammika Malsinghe, Additional Secretary, Ministry of Wildlife and Forest Conservation (MWFC)

Article on park written by- Hasini Sarathchandra, Chief Media Officer, Department of Wildlife Coservation (DWLC), Mahesha Chathurani Perera (Graduate Trainee), (DWLC)

Tamil Translations- A.R.F. Rifna, Development Officer, MWFC

English Translations (Documents)-Asoka Palihawadana, Translator, MWFC

English Interpretation (Story)-Thanuka Malsinghe

Web Designing-C.A.D.D.A. Kollure, Management Service Officer, MWFC

Photography-Channa Suraweera, DWLC